OpenClaw's Hype Is Burying the Real Product Story

A teardown of the five hidden product bets that turned a weekend project into a bidding war and what they reveal about building real agents people actually use.

175,000 GitHub stars in under two weeks. A bidding war between Meta and OpenAI. Cloudflare stock surging 14%. And as of this weekend, the creator joining OpenAI to bring the vision to everyone. You’ve heard the OpenClaw hype. The coverage has been either breathless or instructional. Nobody’s doing the product teardown. So I dug through the codebase, the Lex Friedman and YC interviews, Armin Ronacher’s technical blog post on Pi, and community architecture breakdowns. What I found: OpenClaw embeds five product bets that most teams building agents are making accidentally, if they’re making them at all. Each one represents a fork in the road each PM will face too. If you’re a patient reader, the last two are the ones I think most teams are getting wrong.

Lets dive straight into it.

1. Markdown as Memory: The Bet Against Vector Databases

Most agent frameworks store memory in vector databases. Embeddings, semantic search, the whole retrieval-augmented generation stack. OpenClaw stores everything as plain Markdown files and JSONL transcripts in a directory on your machine.

Your agent’s long-term memory lives in MEMORY.md. Its personality is in SOUL.md. Daily conversation logs are in YYYY-MM-DD.md files. You can open them in any text editor, version them with Git, grep through them, or delete them.

For search, OpenClaw uses a hybrid of 70% vector similarity and 30% keyword matching. But the source of truth is always the human-readable files.

The product decision this embeds: Memory should be inspectable, portable, and owned by the user. Not locked in a proprietary database that you can’t audit or migrate.

Why this matters for your product: If you’re building any agent feature that stores user context, ask yourself: can a user see what your agent “knows” about them? Can they edit it? Can they take it with them if they leave? OpenClaw’s answer is that memory is a user-facing feature, not a backend implementation detail. The file-based approach also makes debugging straightforward. When your agent acts weird, you can literally read what it remembers and see what went wrong.

The tradeoff is real, though. File-based memory works beautifully for a single user’s personal agent. It starts to strain when you need semantic recall across massive corpora, or when multiple agent instances need to share state. One community developer wrote about augmenting the default system with a more sophisticated cognitive architecture because the out-of-the-box memory wasn’t enough for complex workflows. That’s the tension: simplicity and auditability vs. sophistication at scale.

2. Deliberately ignoring MCP: Let the Agent Write Its Own Tools

This is the most provocative architectural choice OpenClaw makes, and the one that generated the most debate after Steinberger’s YC interview.

OpenClaw doesn’t use MCP (Model Context Protocol) natively. There’s no built-in MCP support. And this isn’t a gap they haven’t gotten around to filling. It’s a deliberate philosophical stance.

Armin Ronacher puts it directly: the omission of MCP “is not a lazy omission. The entire idea is that if you want the agent to do something that it doesn’t do yet, you don’t go and download an extension or a skill or something like this. You ask the agent to extend itself. Echoing the idea of code writing and running code.”

Steinberger echoed this in the YC podcast: giving agents tools humans already use (like CLI commands) is more effective than inventing special protocols for them. His punchline: “No human would be willing to manually call the complex MCP protocol. Using CLI is the future direction.”

Instead of MCP servers, OpenClaw uses a SKILL.md system: Markdown files with YAML frontmatter and natural-language instructions that the agent reads and follows. Skills are modular, human-readable, and shareable through ClawHub (a community registry). More crucially, the agent can write its own skills. Ask it to do something new, and it’ll draft a SKILL.md, save it, and start using it immediately. No restart required.

The product decision this embeds: Extension through code generation rather than protocol integration. The agent doesn’t need pre-built connectors to new services. It needs the ability to write code and run it.

What this means for your product: This is a genuinely different mental model for agent extensibility, and it’s worth sitting with regardless of where you land on it.

The MCP model says: build standardized connectors so agents can interact with tools through a common protocol. It’s the API economy applied to agents. Structured, predictable, controlled.

The SKILL.md model says: give the agent the ability to read, write, and execute code, and let it figure out how to interact with anything. It’s more like hiring a capable developer and pointing them at a problem, rather than giving them a pre-wired integration.

Each approach makes a different bet about where we are in the maturity of agent systems. MCP bets on standardization, interoperability, and safety through structured boundaries. SKILL.md bets on the raw capability of LLMs to write correct code on the fly, and that this capability will keep improving.

For product teams making extensibility decisions right now, the question is: do you trust the model enough to let it write its own integrations, or do you need the safety rails of a structured protocol? Your answer probably depends on your user base, your risk tolerance, and how mission-critical the tasks are.

3. Serial Execution by Default: Reliability Over Speed

The SKILL.md decision is about how the agent gains new capabilities. This next decision is about how it executes them. That’s an architectural choice that runs completely counter to the “make it faster” instinct most product teams have.

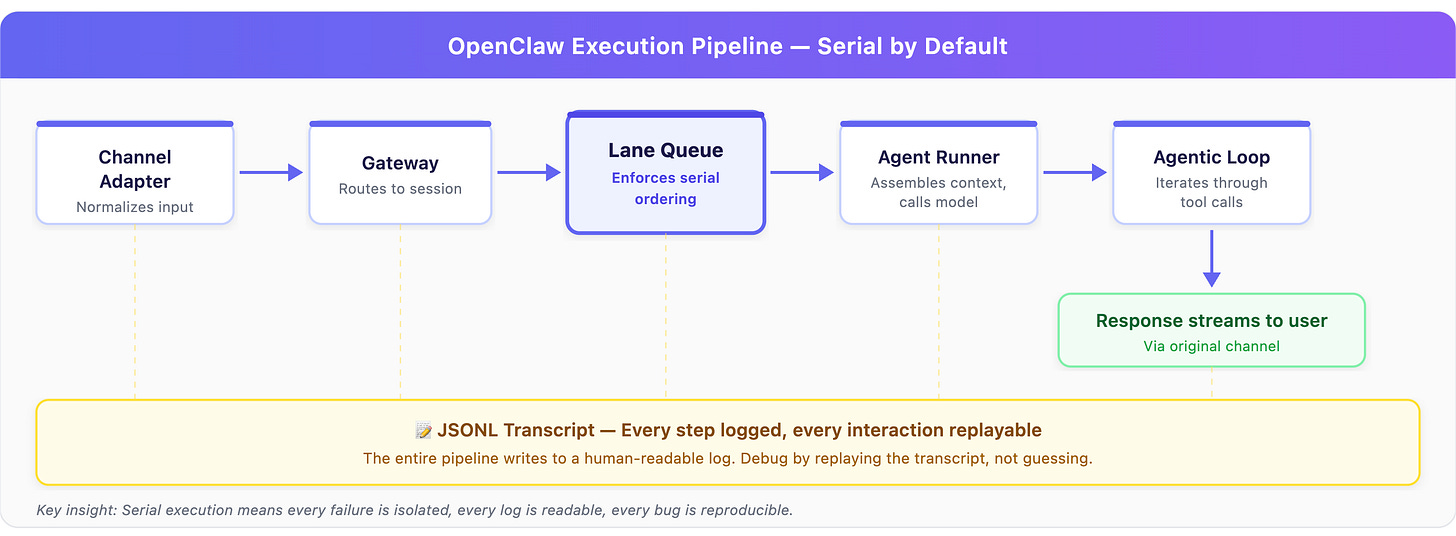

OpenClaw’s Lane Queue system enforces serial execution by default. Every message within a session is processed one at a time, in order. Parallelism is only allowed for tasks explicitly marked as low-risk and idempotent.

The pipeline is strict:

The product decision this embeds: Predictability and debuggability matter more than throughput for a personal agent.

Why this matters for your product: Most developers building agents encounter the same failure pattern. Messy concurrency creates ghost bugs. Two tool calls interfere with each other. State corrupts silently. The agent acts on stale context because a parallel operation updated something mid-task.

OpenClaw’s response is to make serial execution the boring, reliable default. This means your agent might be slower when handling multiple requests, but every failure is isolated, every log is readable, and you can replay the entire JSONL transcript to reproduce any bug.

If you’re building agent features, this is worth internalizing: the bottleneck for production agents isn’t usually speed. It’s reliability. Less than 25% of AI projects make it from pilot to production (a stat that comes up repeatedly in enterprise AI discussions), and a huge chunk of that failure is due to non-reproducible behavior. OpenClaw’s bet is that an agent that’s slower but predictable will win over an agent that’s fast but occasionally breaks in ways you can’t debug.

4. The Interface Layer Split: One Brain, Many Mouths

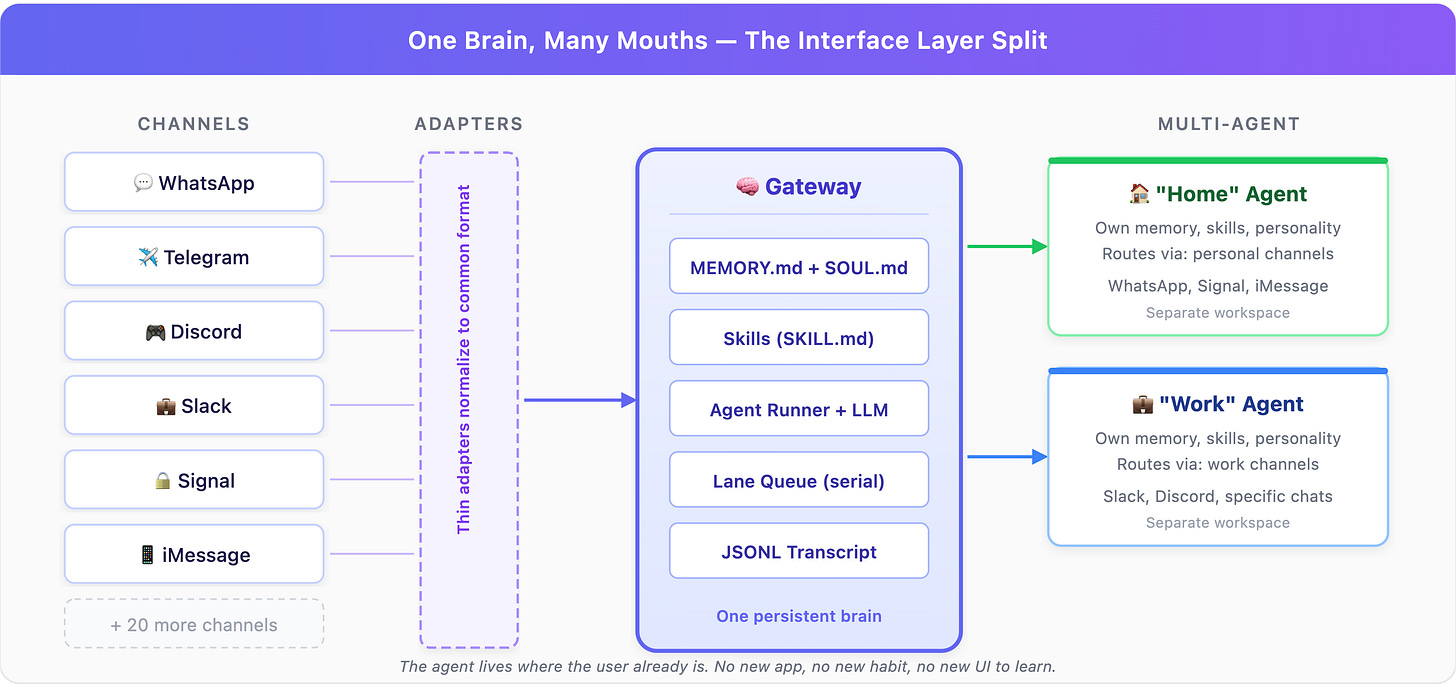

OpenClaw separates the interface layer (where messages come from) from the runtime layer (where intelligence lives). This sounds like obvious architecture, but the product implications are significant.

Your agent has one persistent brain (memory, skills, personality) accessible through WhatsApp, Telegram, Discord, Slack, Signal, iMessage, and 20+ other channels simultaneously. Each channel gets a thin adapter that normalizes messages into a common format. Adding a new channel means writing one adapter, not touching any agent logic.

Multi-agent routing takes this further. You can run multiple agents on one Gateway, like a “Home” agent and a “Work” agent, each with their own workspace, personality, skills, and memory, routed by channel, account, or even specific group chat.

The product decision this embeds: The agent should live where the user already is, not force the user into a new app.

Why this matters for your product: This is the design choice that, more than any other, explains why OpenClaw went viral. Steinberger built a personal assistant that lives inside the messaging apps people already use every day. There’s no new app to download, no new habit to form, no new UI to learn. The user’s mental model is just: “I’m texting my assistant.”

As Steinberger told Lex Fridman, the magic clicked when he was using it in Marrakesh over shaky mobile internet. WhatsApp just worked, even on edge connections. He wasn’t thinking about the agent as software. He was just asking for help.

For any PM building agent features: where does your agent live? If the answer is “inside our app,” you’re competing with every other app for the user’s attention. OpenClaw’s counter-bet is that the agent should be ambient, present in the tools you already have open. This is the same insight that made Slack bots powerful: don’t make users come to you.

5. Semantic Snapshots: How the Agent “Sees” the Web

When OpenClaw’s agent needs to browse the web, it doesn’t take screenshots and send them to the model (the approach most agent frameworks use). Instead, it parses the accessibility tree of a page and creates a structured text representation. They call it a Semantic Snapshot.

Instead of a 5MB screenshot, the agent gets something like:

- button "Sign In" [ref=1]

- textbox "Email" [ref=2]

- textbox "Password" [ref=3]

- link "Forgot password?" [ref=4]That’s roughly 50KB. Same actionable information. The agent references elements by ref numbers (”click ref=1” to hit the Sign In button).

The product decision this embeds: Token efficiency is a first-class product concern, not just an engineering optimization.

Why this matters for your product: Every time your agent processes a screenshot, you’re burning tokens. And that’s real money. A semantic snapshot is roughly 100x smaller than a screenshot. Across thousands of web interactions, that’s the difference between an agent that costs dollars per day and one that costs cents.

But the advantage isn’t just cost. Precision goes up too. An agent clicking pixel coordinates based on a screenshot is inherently fragile; slight layout changes break everything. An agent clicking ref=1 on a structured accessibility tree is interacting with the semantic structure of the page, which is far more stable.

If you’re building any product that involves agent web interaction, semantic snapshots (or something like them) should be on your roadmap. The screenshot approach works for demos. It doesn’t work for production agents that need to be reliable and cost-effective at scale.

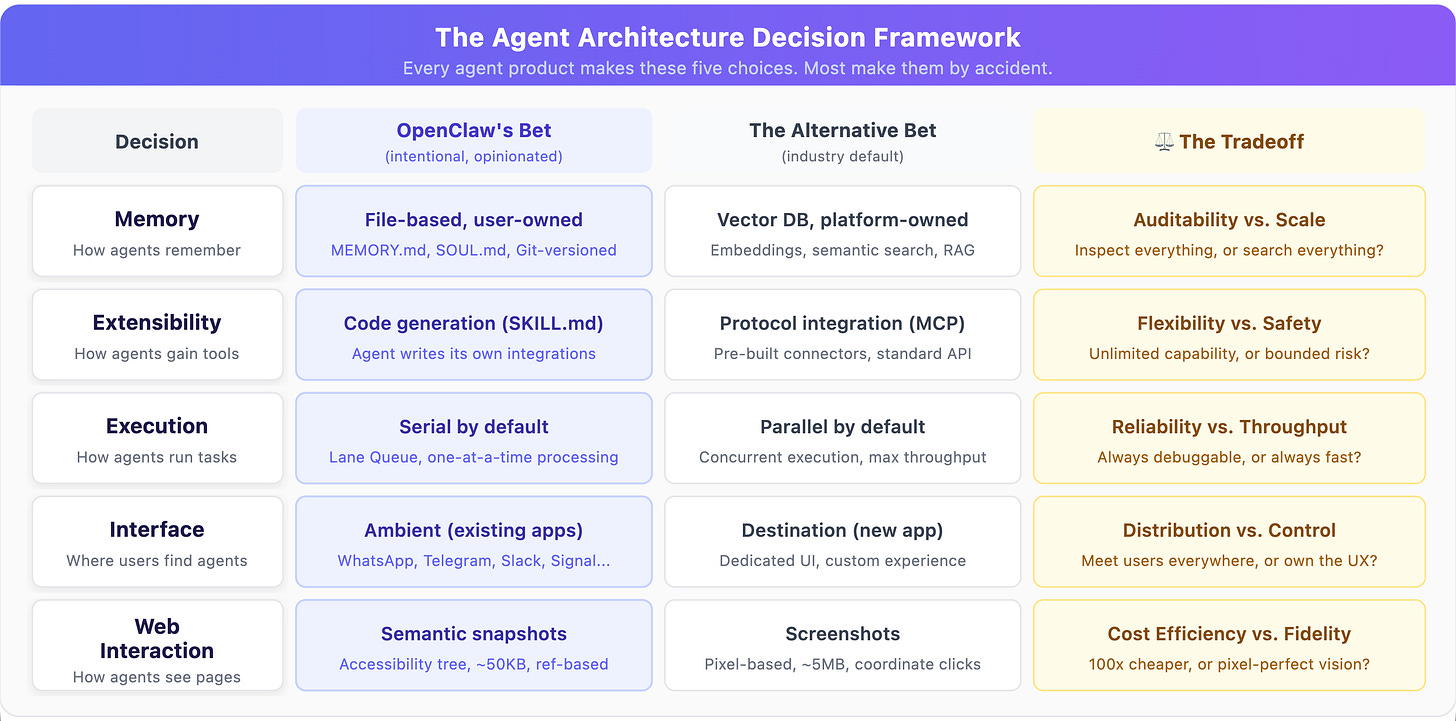

The Bigger Picture: Architecture Is Strategy

These five decisions aren’t independent. They form a coherent product philosophy that I’d summarize as: give the user a capable, transparent, locally-owned agent that extends itself through code generation rather than protocol integration, prioritizes reliability over speed, meets users where they already are, and treats cost efficiency as a product feature.

Here’s the framework I keep coming back to when evaluating any agent architecture, whether it’s mine, yours, or OpenClaw’s:

No column is objectively right. But every agent product makes an implicit choice in each row. The problem is that most teams make these choices accidentally, by inheriting framework defaults, rather than deliberately. OpenClaw is instructive precisely because every choice was intentional and traceable to a product value.

The question for your product team isn’t “should we copy OpenClaw’s architecture.” It is: what are the product values your architecture embeds, and are they the right ones for your users?

Because architecture is product strategy expressed in code. OpenClaw just happens to make that connection unusually legible.

OpenClaw is moving to a foundation structure now that Steinberger has joined OpenAI. What happens when the most opinionated open-source agent architecture meets the resources of the biggest AI lab? That’s the story worth watching, and I’ll be covering it as it develops.